Beauty is not a quality in things themselves; it exists merely in the mind which contemplates them; and each mind perceives a different beauty.

Between the diagram and shape making

The practice of urban design finds itself at particular juncture today. On the one hand, rapid urbanisation, particularly in emerging economies, has intensified an urgent need for good planning and the development of successful urban centres. There have been few times in history when the skills of architects and urban designers have been more needed as now, as world's population becomes its most urbanised. On the other hand, there is a somewhat justified scepticism within the profession and beyond of the capacities of architects and planners to produce required responses to the formidable challenge of rapid urbanisation. The disappointment in the failures of the past 50 years of urban design has resulted in a crisis of confidence in our collective capacity to plan successful cities.

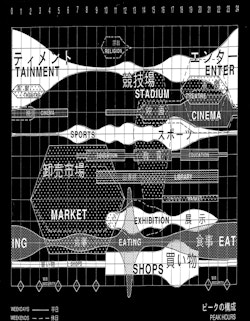

OMA: Yokohama masterplan

In recent times, the most common answer to this problem has been a paradoxical combination of diagrammatic rationality and free shape making. The proliferation of data-informed design has attempted to capture the multifaceted and complex aspects of what makes a city a city into a rational and understandable set of diagrams. From patterns of habitation to density to land values, vast amounts of information can now be translated into diagrams, which more often than not, become the actual form of urban plans. The rationality of the information behind these diagrams conveys a degree of objectivity to this approach. Yet it goes without saying that the urban condition is not reducible to a set of diagrams, let alone their literal translation into physical form. Hence, the schematic character of most recent urban plans can be explained in part by their diagrammatic origin, having not been yet enriched by seemingly less rational qualities such as sense of place or character.

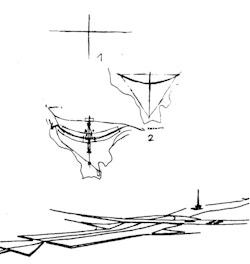

Lucio Costa: Brasilia, initial sketch

This helps to explain another aspect of current city making: the reliance on shape making. The fascination with iconic buildings post Bilbao as a place making tool that is not just exclusive to individual buildings. Worryingly, there are many masterplans today that purely rely on form, most of the times two-dimensionally in plan, as the mechanism to give identity and character to a new piece of city. The grand gesture becomes an all-encompassing element, explaining and at the same time representing the idea of the city. Hence, contemporary masterplans of sweeping curves, allegorical circles or other formal devices; not that this approach is entirely new as Brasilia or Chandigarh testify. Yet it goes without saying that most successful urban places are not easily reducible to a simple gestural form, instead they are the result of a more complex, and at the same time, subtler set of rules.

Madinat al Irfan advances a response to these same challenges with a different approach. Whilst incorporating data informed design and not shying away from formal gestures where actually needed, the masterplan draws both from the picturesque and townscape traditions to propose a place that is fundamentally grounded in the actual spatial experience of the city: the urban picturesque.

Madinat al Irfran: Central Square

Beyond the plan

Madinat al Irfan is a landscape-led maserplan. Not only is the main urban strategy devised from the actual landform, but the spirit of compositional approach behind the project is decidedly picturesque. This approach is primarily structured around three key topics: the composition of pictures, memorable images of the city or landscape; the spatial, three-dimensional nature of these images, and finally an aspiration to a sense of the un-designed, the naturalness of the end product; as if these places had always been there.

Both in the English landscape tradition typified in the work of Capability Brown and the townscape movement in the UK as represented by Hubert de Croning Hasting, Nikolaus Pevsner and Gordon Cullen, there is clear primacy of the visual and spatial composition over the two-dimensional order of the plan. Madinat al Irfan follows the lineage of this tradition: the specific aspects of the place, the site, the topography, but also the particular urban configurations of the region are brought together with a decided sensitivity for the picturesque where the plan is the result of the place and not the other way around.

"At once, romantic and rational"

At the heart of this notion, there is a double subjectivity. The visual nature of the composition, of the painterly image in the landscape, implies a subject that looks at it, completing and understanding the composition by the very act of seeing it. In the case of the landscapes of Capability Brown this process unfolded from clear vantage points within the properties for which he was designing a landscape: from a belvedere in a terrace or a particular window from a manor house. These key views around which the landscape is structured also imply a spatial, three-dimensional understanding of the composition. The careful balance of a tree, a mound, a stone wall and a creek, only makes sense when seen and experienced, not when laid out in plan.

Experiencing this kind of balanced composition is highly personal, hence the second element of subjectivity. Rather than having a rational, geometrical order imposed on the land, as in the French landscape tradition, the concern for the picturesque relies on the individual designer’s sense of composition in place. The picturesque and the appreciation of it owes its aesthetic authority to a sensible mise en scene of objects, masses and voids artfully put together by someone, where space, matter and order, but also chance, collage and juxtaposition all play their part.

At its heart, there is a delightful paradox here as, the ultimate aspiration of a picturesque approach is to disappear, for a place to become so naturally there, to feel as if it has always been there. This is the result of a most difficult balancing act: designing a place in such a way which will blur the fact that it has even been completely designed. In that very moment, the traces of the personal might be erased or forgotten, and the place will just be.

Despite the poetics, this aspiration is not without fundamental challenges. Is it possible to achieve in a contemporary project the level of naturalness that traditional cities achieved as a by-product of their passage through time? It is possible to design and codify, in the case of a masterplan for a new city, the sense of place and character we feel in existing ones which have long been successful?

Formality and informality

As in any masterplan, Madinat al Irfan organises a development quantum within a given, defined site area. It takes into consideration different kinds of data: from the path of the sun, direction of the wind and other climatic aspects, to population estimates, market profiling or forecasts for transport demand. Whilst the analysis of this considerable amount of information certainly informs the masterplan response, these data do not fully explain the compositional aspects that underpin the design, less alone the character of the place proposed.

Clear design decisions at the very beginning of the project established the primary place making strategy: a city of bridges above a wadi park; a collection of villages on the hillier topography in the southern part of the site; two compact downtown areas in the flatter areas at the north of the site. It goes without saying that this did not have to be the only way to layout the quantum of accommodation within the limits of the site, as the different competition entries testified – each had done it differently. These particular design strategies were a specific response to site and brief but also had a particular sensitivity to the place; both the existing one and the one to come.

Several reasons behind the design strategies are easily explainable and almost self-evident; flatter, larger areas lent themselves to the placement of the densely populated downtown areas with bigger footprints and taller buildings. Following the contours of the hills imply curvy, sinuous roads, which are the base for villages. The wadi collects water and is a natural green spine, which can easily then become a natural park. Other aspects are mostly defined on terms of character, sense of place, hierarchy, views and composition and these cannot be completely explained in purely functional terms: from the location of the main mosque as a focal point of the Wadi Park, to the sequence of bridges defining park ‘rooms’, from the different character of the two sides of the wadi to the silhouette of the villages and hamlets against the backdrop of the Hajar Mountains.

Perhaps one singular theme explains the design sensitivity behind all these compositional decisions: a continuous tension and balance between formality and informality. The Madinat al Irfan masterplan enjoys and exploits the place making benefits of contrasting compositional devices, providing diversity but also intensifying the aesthetic experience of having different elements side by side. For example: the relative order and gridded nature of the downtown areas is counterbalanced by the informal arrangement of the villages and hamlets; the naturalistic environment of the Wadi Park is enhanced by the sequence of straight lines of the bridges connecting each of its sides; the meandering character of the souk district is a spatial foil to the clarity and formality of the nearby CBD square.

In the juxtaposition of these diverse and contrasting sets of places and formal strategies lies a key to the sense of place of Madinat Al Irfan. Nowhere is this more clear than in the series of ‘walks’ through the city that were developed as the masterplan was emerging. Both a design tool and a representational method, the walks illustrate the experience of the city as a pedestrian moving through the different districts and spaces of Irfan. This sequential technique demonstrates the likely experience of the formal and informal as people walk through the city. But crucially, the representation and modelling of the city has allowed place making strategies to turn into elements that can be codified (building heights, setbacks, key vistas, special corners or locations for public spaces) that will be developed and built by many different hands over the lifetime of the project:. A clear set of parameters informing each block in the city has been devised through a sensitive approach to the site.

Digital picturesque

Finally, the digital realm was explored in the design process. The use of digital techniques opens numerous and novel possibilities to explore and expand the picturesque tradition. These methods of representation and the directness of three dimensional tools allows rapid testing of options and variations from a spatial and three-dimensional point of view. As the plan starts to become just an output to convey ideas, the 3d model and 3d views become the actual design tool and method of representation to plan and understand the city as it will be actually experienced.

In so doing, the Irfan masterplan has been designed three-dimensionally. Whilst this might seem almost self-evident when designing a city, what this actually signifies is that the city is the result of a spatial, three dimensional understanding of the urban form and its experience, rather than just a two-dimensional composition of a plan. Topographical contours, the massing of the building or the solar path have been taken into consideration to produce a three dimensional planning that has been calibrated by literally moving through the spaces of the scheme.

This approach revealed something special in the design development: there was a sense of discovery of the spaces as we ‘walked’ through them, which opened up an iterative process in which the massing, configuration and ultimately the plan were all refined by the vistas and views of the sequential movement across streets and pedestrian alleys. This virtual promenading has produced changes, accents that informed the design codes of the city, giving way to special moments, key views or adjustments of massing that would have been impossible to acknowledge and address in a purely two-dimensional representation.

Digital tools join the lineage running from the images that are at the heart of the picturesque landscape tradition to the sequential planning behind the townscape movement, putting at the centre of the process of designing cities the most simple and fundamental act of the urban life: experiencing it.