Chelsea College of Arts

Central St Martins

London College of Communications

London College of Fashion

Evolving one university across multiple sites of regeneration.

UAL: topologies and typologies

As a practice, we have been active participants in a live and fortuitous experiment - one which evolved by happenstance and circumstance. The experiment takes the form of four separate commissions relating to a single institution: The University of the Arts London (UAL). And, the conditions of this experiment are quite unique. Firstly, in its ambition: a newly formed university, UAL, seeking to redefine its cultural identity while simultaneously reimagining its physical estate. Second, in its timeframe: Allies and Morrison began its engagement with the experiment twenty years ago and, thanks to its incremental success, it is still unfolding today. Thirdly, through the insights it can reveal about the relationship between knowledge production and a 21st century city such as London.

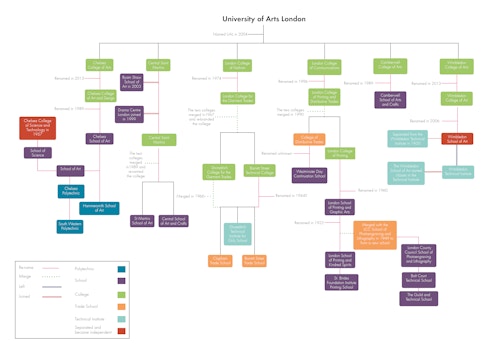

By the late 20th century, the governance of these independent, specialised and prestigious colleges converged under the auspices of the London Institute. In 2003, the London Institute was granted university status and degree awarding powers - a major turning point in its history. A new university, UAL, was formed with six constituent colleges comprising: Central St Martins, London College of Fashion, Chelsea College of Arts, London College of Communication, Camberwell College of Arts and Wimbledon College of Arts. This consolidation was regarded as a triumph for London’s cultural capital by industry leaders at the time. Sir Terence Conran wrote at the time:

The sciences, business management and social sciences all have great universities championing their subjects. Small arts and design colleges, which contribute much to the quality of our lives, also deserve a world class university. They have brought the arts and design to where we are today - a university will give them the stature they now require nationally and internationally.

Unlike most traditional urban universities, however, UAL did not inherit a central campus. Its facilities were never walled off from their surroundings. Its estate was never masterplanned and its eclectic buildings were not designed in relation to one another. Nor was its history rooted in a single neighbourhood or community with a clear identity. Dozens of unique and relatively independent schools were consolidated into six by the start of this century.

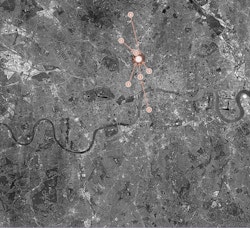

In this sense, UAL’s porous and fragmented condition has parallels with the evolution of London itself - which began as a constellation of discrete settlements. Through centuries and waves of urbanisation, this multitude of historic towns and villages gradually coalesced into a global city. Although it may appear singular and continuous, London remains a polycentric city. Perhaps one of its main strengths lies in the heterogeneity of this character, the diversity of its people and the creative interaction between these ingredients. Likewise, UAL operates as a network of unique, hothouse environments bound by an overarching governance structure. The whole is more than the sum of its parts.

But UAL had to think very carefully about how to balance this singular yet plural identity in the process of rebranding and redeveloping its estate across very different sites and contexts in London. In this, it is an interesting study in topologies and typologies. As architects, we are quite familiar with the latter when we design new or mutate existing building types. Thinking about our projects through a topological lens, however, offers a new perspective. In network theory, a topology describes how different parts of a system are related to each other. In mathematics, the term describes the properties of an object that remain unaffected by continuous change. It doesn't take a huge leap to see how these concepts are relevant to UAL’s collegiate structure and the iterative transformation of its estate. The frames of typology and topology raise the question: what aspects of the experiment have remained constant across the four projects - and which have changed? The city, the client, the broad spatial programme, the nesting of a university within a wider context of regeneration and, of course, our own approach to masterplanning and design have all been constants.

Despite these fixes, there have been a number of variables as well. For example the particularities of each site, the distinctiveness of the local context and the quality of existing buildings have all varied significantly. The individuality of each college and their specific spatial requirements have also varied, as well as the academic identity and creative output of each artistic community. Our interface with this institutional context has taken the form of four independent commissions involving infill development, a masterplan, refurbishment and new-build schemes. They suggest how our approach to designing urban universities has led to new topologies and typologies for London.

Chelsea College of Arts

In 2003, Allies and Morrison was commissioned to design the new Chelsea College of Arts. Seizing the opportunity to move more centrally to a prominent site next to the Thames from various locations in west London was a decisive moment in the history of the college. Thanks to UAL’s influential contacts, the New Labour government was persuaded to sell the state-owned former Army Medical College to the university instead of house builders Berkeley Homes or the Aga Khan Institute - both of which were rival bidders with much deeper pockets. The Government could justify selling the land at a discounted price in part because of the public benefit of bringing a prestigious arts college next to Tate Britain, reinforcing the area’s cultural presence.

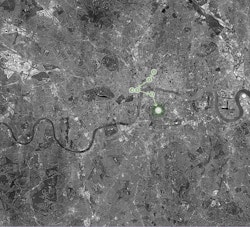

Location diagram, Chelsea College of Arts. Past locations: Southwestern Polytechnic / Chelsea Polytechnic / School of Art (1), Hammersmith School of Art (2), Chelsea School of Art and Technology (3).

Our urban approach to the site involved a few key moves. First, to dismantle the 12-foot security fence around the perimeter which made the site impenetrable. Second, to open up the former parade ground to the public, revealing a major new square for London framed by elegant Edwardian facades. Third, to link the college directly to the new Tate entrance (a scheme that we had completed for the museum a year earlier) via an underground passage.

Architecturally, our response was simple: intervene as little as possible and repair the existing fabric at the edges to make the old army buildings less defensive and more accessible. To achieve this, the existing buildings were cleared of many low-grade, piecemeal extensions, and new, acupuncture-like insertions were introduced in the form of small, flexible studio spaces.

From Army Medical College to arts college

Another priority was to remove anything getting in the way of circulation. The backs of the barracks, previously a collection of escape staircases and lavatory windows, were reorganised and extended to present a new face to neighbouring streets and buildings. Separate external stairwells were also added to improve access to each building, resulting in more open buildings without cores inside. New studio spaces were built beyond the old barracks, with daylit workshops against a massive penitentiary wall transforming a neglected courtyard. Moving from purpose-made arts buildings into something which was found and repurposed served the UAL well at a time when British society was increasingly captivated by contemporary art that was responsive to its environment rather than abstract or detached like the abstract expressionism that typified 20th century Modern art.

Much of the student work that came out of the new Chelsea School of Arts in the early years was to do with the Edwardian building itself or the occupation of the courtyard which became a de facto exhibition for installations. In this sense, our architecture was - intentionally - secondary: it served as the backdrop to urban life and creative expression rather than taking centre stage.

Chelsea College of Arts and Tate Britain

Central St Martins

Bringing the art school Central Saint Martins, arguably the jewel in the UAL crown, to King’s Cross is widely recognised as an urban and commercial masterstroke. Set within the reimagined old granary (built 1851), it is an anchor in our King’s Cross masterplan. Refurbished and extended, the new college building itself was designed by Stanton Williams. Bringing Central St Martins to King’s Cross came about thanks to a chance encounter between the right people from UAL and Argent - the developer and our client for the masterplan of this major site.

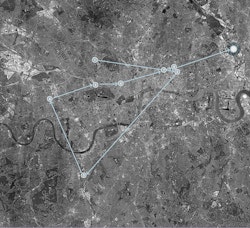

Location diagram, Central St Martins. Past locations: Central School of Arts and Crafts (1), St Martins School of Art (2), Drama Centre London (3), Byam Shaw School of Art (4).

With the backdrop of the 2008 financial crisis, the university was able to commit to moving to King’s Cross at a time when other businesses were unable to. The UAL’s presence alongside two major railway stations, the Eurostar, Regents Canal and a wealth of heritage and open space a prime central London location is now an attraction for tech and other employers engaged in a territorial race for talent. We shouldn’t understate the radical transformation of King’s Cross. It was a void in the city, a place that was entirely out of reach, out of sight and out of mind for the ordinary Londoner. The area underwent significant post-industrial decline and had become a desert and haven for drug dealers and prostitution. Not an obvious location for public activity or an arts school.

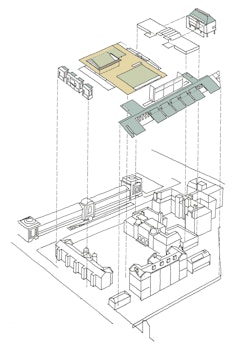

To address this severance, our masterplan proposed to weave a network of new streets, extending surrounding routes, knitting the area into its surrounding fabric. The masterplan reconstitutes the historic grain that had been erased and allows for a more granular morphology to emerge. Another principle of the masterplan was to breathe new life into the relics of industrial heritage dotted across the site. Grade II listed, the granary building was built as a Victorian transport interchange for the transfer of goods from horse drawn canal boats to the rest of the country via coal powered trains.

King's Cross masterplan (left) and siteplan of Central St Martins within the masterplan (right)

We knew that both offices and housing would fail to deliver the lively pattern of life intended for the granary and the public space in front of it, so well before UAL came into the picture, our masterplan kept this piece of the puzzle intentionally loose. Instead, the plan prescribed a generous public realm to hold the granary and its forecourt together. This landscaped armature integrates the development parcels with surrounding spaces and neighbourhoods. Each parcel has a defined range of flexibility regarding uses, density and, crucially, the active frontages. This meant we could open up what would otherwise have become a black box facility into an outward looking urban university.

Today, Central St Martins brings a civic quality, energy and activity to King’s Cross, as thousands of lively students flow in and spill out onto granary square to join local families, workers or visitors. The porosity of the university, the decision to traverse a semi-public street across its lobby and limit the use of access cards to well within the building has meant that city life is now permanently drawn to and through this UAL faculty. People of all stripes come to learn, for meetings, for end of year shows or out of sheer curiosity.

Central St Martins overlooking Granary Square

London College of Communication

The London College of Communication (LCC) hasn’t strayed far from its original trade school homes and settled into Elephant & Castle by the 1960s. Formerly known as the London College of Printing, LCC offers degrees in visual communications, graphic design, advertising and other creative disciplines with students graduating largely into the creative industries.

Location diagram, London College of Communications. Past locations: The Guild Technical School (1), St Bride's School (2), Bolt Court Technical School / London College of Printing and Distributive Trades (3), Westminster Day Continuation School / The College of Distributive Trades (4).

This is a place we know well as our involvement with LCC has been twofold and over two generations. Firstly, we completed an extension and renovation of their 1960s building at the turn of the 20th century, and now, we have been involved in building an entirely new home for LCC across the street from its current location which is currently onsite. Elephant & Castle, once known as the Piccadilly of the South, is a busy interchange and roundabout in south London; several Underground and rail lines pass through its station. The area underwent significant change following the war, suffering bomb damage and it became the site of a large Modernist complex, the Elephant & Castle shopping centre, which until a year ago occupied the eastern side of the site. LCC had a similar Modernist aesthetic and sits on the western side.

London College of Communication (built 1964), with entrance by Allies and Morrison (2001)

We were, as architects, having conversations with two different actors looking at these two sites. There was UAL needing more capacity for their building, but our analysis showed that it couldn’t take any more extensions. Meanwhile, we were working with Delancy on a new town centre scheme - which looked to redevelop the shopping centre site as a mixed use development. The site didn’t quite give them everything they needed, but then the two clients met and this led to a joint venture.

The new LCC is moving to the east side, taking a new place as part of a wider mixed use development, serving as its anchor. It will be set within an outdoor retail galleria, high density housing and one of London’s busiest transport interchanges. On the west side, the existing LCC building will be demolished, the land reused as further mixed use development. The project aims to restore the pre-war grain of the city at ground level with new walkable routes and a more human scaled ground floor experience that the 60s era mega structures had erased.

West site (current LCC)

East site (future LCC)

Elephant & Castle under re-development today

For the new LCC, our response has been to design for them a distinctively urban building. It incorporates a new Northern Line entrance for the Underground station at its base with 11 stores containing the entirety of the college, the home for UAL’s administrative head offices which will move here from Holborn, and the Stanley Kubrick Archive. There will be a public base of three levels. Dramatic circulation stairs around a massive atrium bring students and faculty, those with UAL pass cards, past a threshold into the upper seven levels which provide the more cloistered spaces of university life. It is a hybridised building housing a broad spectrum of creative spaces from traditional printing to video gaming to photography to digital and graphic design. The design brief aim was to overcome departmental silos, by providing opportunities for chance encounters and serendipity across disciplines.

The outward expression reflects the grid of type printing processes, an allusion to its roots as a printing school; the patterns of letterpress giving form to the facade. We have reinterpreted this with large precast masonry slabs double height, black in colour, with vertical sliced windows - large and crossing floors - providing people with a view in. The result is less a traditional college and more an urban cultural centre. The project has also allowed LCC to stay rooted in its Elephant & Castle home, but now with a bold new identity.

London College of Fashion

Due to open in its new Stratford home in autumn 2023, the London College of Fashion (LCF) is a constituent college of UAL offering courses across the breadth of fashion, from fashion design to the business of fashion, fashion history, branding and related disciplines. Our task as architects has been to create their first new joint home. Currently they operate in six different locations across London. Each has its origins in a trade school.

Location diagram, London College of Fashion. Past locations: Barret Street Trade School (1), Shoreditch Technical Institute for Girls (2), Clapham Trade School (3), LCF Lime Grove (4), LCF John Princes Street (5), LCF High Holborn (6), LCF Golden Lane (7), LCF Curtain Road (8).

The new LCF is part of a new cultural quarter called East Bank, of which LCF will be the largest building, continuing the tradition of a sort of British grand projet of the cultural variety dating back to the Albertopolis and the Southbank. East Bank occupies a linear site nestled between the River Lea and an infrastructure corridor, overlooking Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, a legacy of the 2012 Olympic Games and the largest new urban park to be built in Europe in 150 years. That site will accommodate four cultural and educational institutions. From north, the V&A East - which will be an east London outpost of the V&A co-curated with the Smithsonian Institution. Then, the London College of Fashion. Then, the BBC Music building, which will be the permanent venue for the BBC Symphony Orchestra. This will be their first permanent purpose built home. Then at the southern end is a new dance venue for Sadler’s Wells - a short walk from University College London’s new Stratford Campus, UCL East. The East Bank site is the jewel in the crown of the legacy masterplan. In this sense, while the LCF building is a big project, it is also one piece of a much bigger national initiative to regenerate what was once an extremely deprived part of London.

Our brief as architects was to create a new LCF that could navigate all the contradictions inherent in the study, production and research of fashion. This is intended to be a working building with a student population of 5,000, and multiple different methods and modes of instruction, including a heavy making component for many courses. So the building has to accommodate this messiness, this chaos even, but it also needs to convey a bold image for an institution that, until now, has lacked a single imageable place.

A factory for fashion between park and city

The architecture, in both form and expression, takes its inspiration from the industrial mill buildings that defined much of east London’s industrial era canals - indeed a vernacular found across the UK: Hard, flexible, robust warehouse buildings - a 21st century warehouse of production. The architecture is unpretentious and robust while capable of containing multiple complex and process-driven internal arrangements that are continually adaptable to change.

It is worth reflecting on where we are in London. The neighbourhoods surrounding LCF and East Bank are among the most culturally diverse in Europe. So, we wanted these buildings to be easy to get into and through for local people. LCF performs an urban role, accommodating a new route to the Olympic Park. It is not a standalone building, part of a wider cultural district. Permeability is thus important and the public can directly access its lower levels and use it as a means of crossing through. As much as possible, we have tried to create adjacencies for interactions between LCF’s neighbouring institutions. We want them to always be bumping into one another. The results could be yet unknown collaborations or creative outputs.

Inside, many different kinds of spaces were needed, from classrooms to fashion studios to exhibition areas to community spaces where the college could interact with the public to quiet areas of research to chaotic spaces for tailoring and making. It is a lot of programme, more than 41,000 sqm required, and it’s a tight site, so this was an exercise in vertical stacking from the start with 14 storeys in total. In this, it has a similar DNA to LCC. There is a generous internal atrium. The first three floors are open to the public. Dramatic staircases criss-cross the atrium and encourage cross-floor interaction. Different departments are assigned individual floors but they share the atrium and public spaces below. The shared core also includes a significant amount of breakout space which is intentionally ambiguous. Who is it for? For anyone who decides to occupy it.

The urban opportunities for the global university

While our journey with the UAL continues to unfold, we have several reflections to share about the changing role of urban universities in the 21st century.

The first is conceiving of university developments as joint ventures with mutual benefits resulting from collaboration between the academic, public and private sectors. Institutions need state of the art facilities in desirable and well-connected locations. Developers want the cultural capital, footfall and prestige that a university anchor can offer. Local authorities value the clustering of civic infrastructure and employment uses that these institutions provide. By coordinating these ambitions and, crucially, having the weight of a commercial partner, multiplier effects can be leveraged. University estates have become more savvy about their influence on major sites and they can leverage this to obtain favourable decisions from local planning authorities, perhaps even obtaining incentivised rates if the land is state or developer owned. A joint venture approach can also ensure that governance, planning and design are well-integrated and, therefore, that university masterplans can be adapted more effectively over time, as demands, requirements, finances or circumstances change.

Linked to this is the need to balance global outlooks with local impacts. Universities are in competition with each other to develop strong industry partnerships, recruit world-class faculty and students as well as secure global research funding and donations. This international perspective is vital but it should benefit (rather than work against) the particular needs of communities where the institutions are situated. Urban universities should be oriented in such a way that maximises the transfer of knowledge for social and economic benefit. Opportunities for inclusive engagement, collaboration, upskilling and employment for local people should be embedded throughout the development process and post-occupancy.

Of the city, not simply in the city: Masterplan proposal for Nalanda University, India

This leads on to a third reflection that universities need to be of the city, not simply in the city in order to thrive. This means designing with an urban ethos in mind. From a design perspective, it can take the form of different tactics: the potential of pre-existing buildings, making built heritage work better, creating street-based forms of development that provide active frontages and remain human in scale. The era of gated, inward-looking enclaves organised around ring fenced lawns has given way to more permeable campuses and learning environments with a mixture of private, public and semi-public spaces. In this sense, the physical form of university masterplans should promote creative, flexible and collaborative use-patterns between different users within and beyond the university.

In order to achieve this, greater emphasis should be placed on the provision and quality of the public realm - physical exchange is vitally important particularly in an era of virtual working. We are living in a time where social interactions - the meaningful exchanges - like the ones we have enjoyed during this conference are needed more than ever. In the drive to attract the best students, staff and funders - the physical places for interaction, discovery and participation (classrooms, galleries and labs, but also those social spaces for the accidental encounters that lead to great discoveries) are vital for institutional success.

Finally, our work is pointing towards the emergence of new building types. Driven by the scarcity of urban land and the desire for density and compactness, spatial briefs for new universities are shifting the dial from sparse, land-hungry low-rise faculty buildings towards more compact, dense and mix-used facilities. The architectural design of this emerging type is driven by diverse functional requirements and blended modes of learning, teaching and conducting research. The result is a sort of anti ivory tower. In its place is a multi-layered building typology that maximises flexibility and collaboration on tight, urban sites blurring the boundaries between city life below and university life above. Here, the faculty building of the future is performing a much broader urban role beyond its core pedagogical remit.

London College of Fashion, Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, 2023

This paper was delivered as part of the Designing Urban Universities conference, hosted by the Department of History of Art and Architecture, Trinity College Dublin, from 22-24 June 2023.