If the new city of Irfan is to be beautiful, it would be a place where people wanted to be. Our starting point therefore is beauty and, for us, beauty evolves from a well-considered composition. That is not something that is deliberately eye-catching or iconic or dominated by a single issue such as sustainability or constructed out of gimmicks to prove it is cutting edge. It is, however, something based on an essential normality, an understanding of place and the value of the space between the buildings being more important than the buildings themselves. Irfan will thus be a composed place, a familiar place and our plan for this new city will set out to be modestly, carefully but unashamedly beautiful.

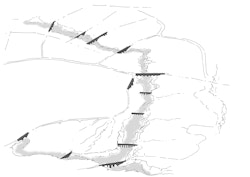

Sequence of bridges over the wadi

In the making of a city, beauty comes from a composition that understands the topography and climatic geography, acknowledges the value history in relation to a modern culture, and manages a straightforward relationship with all of the sensibilities that make cities comfortable, legible and civic. If, in 50 years from now, people say that the city of Irfan is beautiful, its success will depend as much on how it works and how it feels as a place as what it might look like. It will have succeeded if people like it, want to be there and wish to actively contribute to its life. If it can achieve the true benefits of normality then it will be exceptional.

As architects, we trained in the 1970’s – an era when Modernism was questioned and when the style of Post-Modernism offered an easy, if somewhat lazy response to the single-minded rhetoric of rationalism. For us, however, Post-Modernism offered not so much the rejection of Modernism but the inclusion of whatever went before. We felt empowered to be both Modernists thinking about the rational, the economic and the real, and to be Post-Modernists being able to consider history, the culture of a community and a sense of place drawn from the site. With Modernism, beauty seemed rarely referred to. With Post-Modernism, beauty was eclipsed by the reaction to Modernism that defined it. We have been fortunate designing in an era of relative freedom but, whereas, many (well-regarded) architects believe this to offer an unconstrained parametric playground, we believe our limitations are simply extended.

In the early days of our careers, we used to wonder at the drawings and descriptions of an indigenous Arab architecture. It was the world of Bernard Rudofsky's 'Architecture without Architects' - an unselfconscious but supremely confident response to climate, culture and place. We were impressed by an architecture made from materials found close by, that was of its place and timeless rather than an image derived from the magazines of a faraway land. Sadly, that early glimpse into how a local architecture might develop was easily eclipsed by an imported pre-conceived notion of how buildings ought to be - driven not just by budget and the disciplines of project management, but also by an inexorable reflect to make cities and places look like the supposedly successful images of distant places that represented something even temporarily desirable. It was the architecture of imitation in that 'if we can look like them, maybe we can be like them' - a common cultural phenomenon.

"At once, romantic and rational.

All too often, the region’s cities are made from an architecture that is taller than it needs to be, making places that are without shade in a desert environment, using materials that are imported and all planned with an absurd dependency on the car even for even the shortest of journeys. It is an irony that the supposed expression of some newly self-confident nation states is supplanted by an impulse to imitate the very post-colonial architectural culture whose representation may be an anathema to the definition of these emerging political entities. The expression of apparent independence is overwhelmed by the dominance of an imported and often irrelevant way of designing buildings and places. Such city making surely is out of date, without context and without any long-term contribution to a region so needful of a way of thinking that reconciles the enormous need for growth with a culture seeking answers to the problems such expansion poses.

Though Madinat al Irfan may seem a romantic response to what has gone before, it is anything but. It is intensely rational. It is a city that is walkable. The car is not excluded but neither is it dominant. Though there is a loose grid pattern that allows for flexibility and provides a pattern made up of short walkable episodes that lead deliberately to others – an easily developable place that is essentially comfortable and legible. The buildings may be simple and respond to the climate but the spaces they form are complex, revealing and inviting. And though the landscape may be rugged and robust, it provides the basis of the plan. The spaces of this new city are all determined by a landscape that follows the wadi – a wadi that might have divided the city, but here becomes the very determinant that unites it. The scar in the topography made over many millennia becomes the place or the park to which the entirety of this linear city refers.

Though Irfan may have an unfamiliar density in the region, it nevertheless provides a relatively low-rise city with a level of accommodation that addresses the needs of the city of Muscat. It offers an intense juxtaposition of uses that, with a new found flexibility, avoids the sanitising effect of zoning. It is real place to live made from materials that are there, built in forms that respond to the climate and organised with a public realm that avoids the dominance of the car. Planned on the raised plateau overlooking the sea and with a mountain backdrop, the city looks in to the 25 kilometres of retained and reused wadi and, by controlling the flow of water, the wadis become a managed park – a place for recreation and for growing food, a place that all of the new city relates to and a defining characteristic of the new city that unites it. Crossing it will be fifteen inhabited bridges, all occupied viaducts, all devices to provide shade when walking from the main city on one side to the villages on the other, all different in their architectural expression and all deeply symbolic of Madinat al Irfan. This will be a city of bridges - defined by an architecture responsive to place and climate, defined by its relationship to an extraordinary landscape and defined by optimism and a way of planning that brings a new and convincing self-confidence to the culture of Oman. Above all, it will be a memorable place because it will be beautiful.