The landscape

BBC White City, now White City Place

Whether a megacity or a single pavilion, the space underneath and around matters. The placement and orientation of new objects on the landscape should never be arbitrary. Over the last several years, we have been exploring this more with a now well-established in-house landscape architecture team. Our landscape portfolio now spans different cultures and climates, scales and systems, but what all our projects share is the same contextual and place-sensitive approach we bring to our architecture and planning.

Public realm

The spaces between buildings have fascinated our practice from its start. Multiple miniature acts in the public realm can aggregate to have a big impact. Our neighbourhood in Bankside, for example, is a good example. Here, an entire London neighbourhood has been transformed without a masterplan, but through one space, one building, at a time. The area has dis-aggregated through imaginative planning policy which breaks down large blocks by inserting pockets of open space, sometimes public, but more often these have been private, given to the use of the public.

This is a condition we have experimented with in our own studios. The long urban block that had stretched from Lavington Street to the east as far as Great Suffolk Street is now relieved with a cut through an undercroft link to Farnham Place, a lane which we have given back to the city as a publicly accessible walkable street on what was once a service road. Now closed to traffic it has been paved in Dutch bricks and planted with trees.

Farnham Place, London SE1

Waterloo Placemaking Strategy

Down the road, our placemaking strategy for WeAreWaterloo imagines a composition of many small pieces of open space with over 150 illustrative proposed ideas and projects. Each a landscape intervention, they collectively offer a range of practical, attractive and exciting interventions. Collectively, these multiple landscapes could come together to reinforce Waterloo as a significant London destination.

At Tate Britain is evidence of a seemingly minor landscape intervention having a major impact. The landscape design has preserved the historical context opening a new museum entrance through a gradual incision into a semi-basement level. On the Millbank frontage, an adjustment in the alignment of existing railings makes possible a more generous space and a more fluid connection with the gardens either side.

The Manton Entrance, Tate Britain

New types of streets

Streets are changing. They are no longer just through routes; they are important places in their own right. Much of our landscape work is about re-balancing streets in favour of pedestrians, bicycles and the re-animation of urban life.

Staying in our neighbourhood, The Liberty of Southwark is a mixed-use development which has been conceived as an extension of the yards, mews, and streets unique to the medieval fabric of Borough, London. They will be the social setting which will allow the development to thrive. Increasingly, commercial developments in the city will need to mimic the street life of the city to take on the character that people are drawn to.

The Georgian centre of Limerick has a unique patchwork of laneways that could unlock a wider renaissance. Currently utilitarian in function and expression, our strategy re-imagines them as exciting places to be, an alternative meandering route to explore the city centre. Bringing life to these forgotten lanes could catalyse the Georgian neighbourhood’s appeal as a contemporary place to live, work and visit.

Reinstatement of medieval yards and lanes, lined with cafes, shops and market stalls

Limerick Laneways

The overhaul of the Latner Building's ground floor allows the building to engage with the central space

Social landscapes

A major contributing factor to the experience of a place, be it a student at university or an employee in a workspace, is the quality of the outdoor spaces. We are increasingly exploring this in our projects, enriching relationships between student spaces, ecology, sustainable transport, and (the often) historic setting.

At St Peter’s College, Oxford the desire to make an Oxford college feel more ‘collegiate’ involved addressing the college grounds, how quads related to one another and where building entrances could be located to shape a new cohesive heart to the college. Ground floor teaching and reception space of the Latner Building now opens outwards and a new stone arched doorways placed into the side of the neighbouring college chapel make the quad more quad-like. The choice of stone for the landscape draws together disparate buildings unifying them through underlying tones.

Nestled into the arts and crafts conservation area of West Cambridge on a site with mature trees including an orchard over one hundred years old, will soon grow a new model for graduate student housing. For St John’s College, Cambridge, rows of townhouse blocks will frame gardens, meadows, and attenuation lawns. At the heart is a new lane which draws the community together and a surface level sustainable drainage network which runs through the courtyards and out along the lane. Here, we are working as both architects and landscape architects.

Linton Quad, St Peter's College, Oxford

Hinsley Lane postgraduate student housing site, St John's College, Cambridge

The landscape-led city

Landscapes are also three-dimensional interconnected systems – mountains, cliffs, meadows, rivers and sea. The landscape of a new piece of city is similarly three dimensional and complex – roofs, terraces, balconies, gardens, streets, ponds, and rivers. Each level, wall, or surface has the potential to become landscape. Each can perform an important function such as creating nesting habitat, absorbing water, or filtering the air. The most valuable landscapes are those that are not just beautiful and memorable but are also integral in tackling environmental issues such as air quality, water management and carbon sequestration.

We are working on several projects in Ebbsfleet, which will be one of the most significant new towns built in the UK this century. Its urban core is structured around the chalk stream of the River Ebbsfleet, so the landscape strategy aims to bring nature close to home, support biodiversity and natural processes, and nurture the health of residence through opportunities to interact with nature through movement, play and foraging.

Ebbsfleet Central illustrative masterplan

For Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, the largest new park to be built in London in 150 years, the temptation would have been to impose something new. What was a somewhat forgotten river runs down the middle of the site, and this River, the Lea, defines a wider north-south valley watershed. This masterplan rediscovers the intrinsic identity of this landscape. Two centuries worth of back-of-house use, from sewage works and gasworks, power generation, warehousing and goods distribution were situated here, crowding out the Lea’s natural character. The masterplan declutters much of this, bringing out the traces of a meandering valley and its riverbanks. A future landscape has been created that is more like what it was before human industry ever touched it.

Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, London

A 28.9 ha of land acquired by The All England Lawn Tennis Club (AELTC), adjacent to their home in Wimbledon, shapes the future of the Championships. The landscape of the once private, members-only golf club will be restored and enhanced to allow AELTC’s Wimbledon home to expand and contract with the playing season, The golf course infrastructure is being removed to create a green setting in the centre of London for the qualifying rounds of the championships with thirty-nine sensitively incorporated new grass tennis courts, discreet new facilities for visitors and a third show court. Routes and connections across the park will dramatically alleviate crowd pressure on neighbouring streets during the Championships’ two intense weeks each summer while local communities can take advantage of the new biodiverse landscape on their doorstep year-round.

Estate-wide masterplan during Championships and year-round modes

Bringing life to the public spaces of the Al Balad UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Paving detail, pedestrianised street, Al Balad

The cultural landscape

When we read landscape as the ultimate context, the proposition of a new intervention becomes a balancing act, mostly through adaptation, to respond to ecological systems from topography and local planting to the historic and future climate. There is the notion of a cultural landscape to consider as well. We should not forget there is likely to have been an existing design language – one intimately shaped by nature, the need to accommodate a particular climate or the historical availability of natural materials.

The landscape and public realm masterplan for the Old Town of AlUla and Al Jadidah is designed as a series of spaces with a distinct offering that is grounded in AlUla’s unique history as an oasis. Subtle shifts in texture and tone create difference between neighbourhoods and streets and weaves the realm of the town into the adjacent rural landscape. A signature landscape is Qanat Gardens, replacing a roundabout with an open space rich in ecology which incorporates the sophisticated vernacular water management systems in AlUla.

Qanant Gardens, AlUla Oasis

Allegiance Square, Al Balad UNESCO World Heritage Site

We have been working with Saudi Arabia’s Ministry of Culture to develop the Al Balad Public Realm Strategy and Manual. The work is focused at two complementary scales: sitewide strategy and place-specific design guidance. We have also developed the concept design for over four hectares of public realm including souqs, streets, plazas, gardens and neighbourhood squares. The largest of these is Allegiance Square, a new civic plaza at the threshold to this UNESCO World Heritage Site.

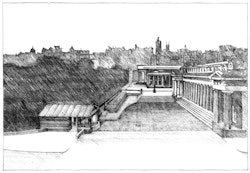

Our first ever project was a landscape proposal. It aimed to gently nudge an open hilltop between the National Gallery of Scotland and the Royal Scottish Academy into a more public role. The winning proposal made more evident the inherent characteristics of the landscape – its hilly topography – and then placed and orientated new pavilions and routes to draw people into and across it. Little or nothing was done to its natural features, but the area has been recalibrated, gently bringing closer together the two buildings framing it. It becomes a civic space yet one which retains the naturalistic character as it was found.

The Mound, Edinburgh