Making heritage work

The meeting of new and old offers intriguing design opportunities. Both the historic and the contemporary should shine yet there should always be a dialogue between the two, whether building in ancient streets, making new buildings next to old or adopting historic structures for contemporary use. In combining them, we can strive for simple, practical, beautiful spaces that, at whatever their scale, seem somehow effortless – making historic places work easily, comfortably, surprisingly.

For the architect or planner, understanding a place’s past is essential, both built as well as intangible heritage. Each historic town or building is a new story to be read and understood. This starts with researching key aspects of its significance, whether in terms of its architectural distinction, its value as a landmark from the past, the communities shaped by it or its role in shaping the identity of a place.

The character of places is often complex and disparate: vibrant and exuberant, or formal and restrained, or anywhere in between. Colours, textures, shapes, silhouettes, architectural styles, rhythms, scale, plot widths and depths, rooflines and pitches all contribute to local distinctiveness. Vernacular materials and details can often play a key role, reflecting local geology, climate and identity.

Today's Chelsea College of Arts, formerly the Royal Army Medical College.

Creative reinvention

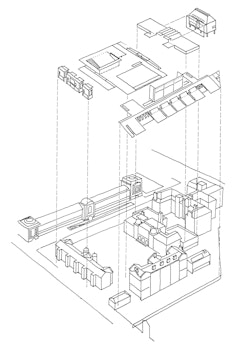

Moving from multiple sites into one was an important moment in the history of Chelsea College of Arts. The College transformed the former Grade II listed Royal Army Medical College, neighbouring Tate Britain, into a thriving place for the arts. The parade ground with its formal Edwardian facades has become a new public space. Spaces within the old army buildings were cleared of ad hoc additions to make robust, adaptable creative studios.

New studio spaces were built beyond the old barracks, with daylit workshops against a massive penitentiary wall transforming a neglected courtyard. The backs of the barracks, previously a collection of escape staircases and lavatory windows, were reorganised and extended to present a new face to neighbouring streets and buildings.

Studio space

New extensions and entrances

New routes

Arsenal football stand, Highbury

Buildings often outlive their purpose. No longer needed as a football stadium, Arsenal’s Highbury stand would surely have been demolished without the protection of its Grade II listing. Converting buildings which have been built for a very specific use is difficult, expensive and potentially uneconomic. Using the scale of the place and its fabric as fundamental parts of its character overcame these difficulties.

The preservation of the building cannot maintain the intangible assets it used to support - the roar of the crowd, the emotion of the match. A new significance was found which links the listed building and the great space it commands: that of a London residential square. The stadium’s fabric was conserved as it was reinvented to provide 725 new homes with the football pitch re-imagined as its new square.

Highbury Square today

A place to call home

Our understanding of built heritage is broad. There are many examples of twentieth century heritage, for example, which need the same care of much older places. And in the interest of the environment, many seemingly unloved buildings can be creatively re-purposed with beautiful results.

Valuing our 20th century heritage

Increasingly, the landmark buildings of the twentieth century are in need of reinvention or evolution. And today there is a growing appreciation of their architectural merit. In 1974, the Royal Festival Hall was the first post war building to be listed Grade I, reflecting the esteem in which it is held as a symbol of post-war revival. However, with time, its auditorium acoustics were failing, its foyers looked increasingly dishevelled, and it lacked an engagement with its riverfront setting. Our understanding of the ideas behind the original design of the building was fundamental to reinterpreting them to meet current and future needs.

This involved a mix of restoration and contemporary changes both inside and out. The foyers were opened up and invasive cafe and commercial units moved into a new linear building that created a new active street in effect. The auditorium was stripped back to the original concrete box and all finishes fixed firmly to this to radically extend the reverberation time. The original colours were reinstated, and bars reopened; back of house, modernised to support a wider range of performance possibilities. Externally, the Hall was reconnected to Queen’s Walk along the river and a line of new restaurants opened up along the riverfront. The internal and external terraces are a huge draw and on days of good weather, the area is busy as never before.

Refurbished Royal Festival Hall

“The throw-away society starts by discarding its richest assets; the ground on which we walk and the buildings we inhabit. The act of constructing a building is so difficult, the environmental cost so large and the cultural effect of occupying it so charged, that we should value those which exist as much as we value the land on which they are built.” - Paul Appleton

Unloved buildings

A building originally designed in the late 1980s as the BBC’s administrative headquarters might seem an unlikely candidate for conservation. Over the years, it had become a dark rabbit warren of a place. Yet even it has been given new life as The Westworks at White City Place, delivering more than 300,000 square feet of new flexible accommodation for multiple occupiers. A series of interventions have improved functionality, increased lettable space and provided an overall aesthetic uplift.

The BBC's White City One by Scott Brownrigg Turner

The existing silver-coloured aluminium cladding was cleaned, dark glazing replaced to allow views into and through the building and a refreshed central courtyard features extended first floor terrace and new cafe pavilion

The main entrance has been moved to open up new routes and facilitate new communal spaces, a cafe and multimedia studio

Within walking distance from our studios, a building that was once a 1960s industrial printworks was transformed into a high-quality office building. Two floors were added, and the core was repositioned to create more flexible spaces. Despite being a refurbishment, the intention was to produce effectively a new building. This was achieved through a thorough analysis of the existing fabric, allowing the implementation of new details for all floors using a straight-forward material palette - its new tiled facade is a special touch.

The Crane Building before retrofit

These projects illustrate a commitment to re-examining existing buildings, regardless of the era they are from, by finding ways to extend their lives by creative intervention, adaption and sustainable re-use.