Living together in the city

Imagine 1,000 neighbours across a few streets of terrace houses. Each resident's experience of the setting is a layered experience. The first layer? Your immediate neighbours to your right, left and across. You're likely to know them. Peel more? There is a second layer. Maybe those down the street, their children may go to the local school, or maybe there is someone there you met at a street party. Then beyond, a third layer? Those bumped into time-to-time at the local shop or down at who you might recognise from your morning commmute. And so, a community web unfolds.

Typical London terrace

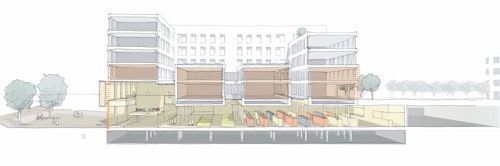

There are opportunities in multifamily buildings, whether mansion blocks or taller buildings, to incorporate this kind of layering both inside and outside: lobbies at ground floor leading to generous communal areas at upper levels; shared open spaces that peel away to uncover more private domains, intermediate territories between public and private.

Another form of layering is to provide for different types and sizes of homes within a single building or block. This allows new development to cater to families of all shapes, sizes and hues, and also opens up opportunities to integrate uses other than housing, but very specific ones that can attract residents, day in and day out - a place to buy a loaf of bread, to bump into a neighbour, to go to the doctor, a place where the kids can run around.

NEW NEIGHBOURHOODS, OLD LAND

The site of the former Hounslow Civic Centre in west London is being recycled to create more than 900 new homes. The first phase, all affordable, is now completed. The project is emblematic of the reuse of well-connected land to create higher density neighbourhoods

Variety of spaces

Many new housing developments now provide for different family types from singles to those with children. In east London, St Andrews was an early vanguard in doing so. A mix of flats and maisonettes (950 in total), wrap around urban courtyards. It is both a shared and domestic space with four layers: Each home has at least one balcony, a private place for a family. The planted courtyard itself, with play space, is shared by residents. There is natural surveillance from the balconies looking in, so parents can keep tabs on their kids below. On the roof there is yet another type of space, designed for quieter moments. The fourth, a public garden on the perimeter, is a place for everyone to mingle.

Private balconies overlooking shared courtyard

Rather than being residual, communal spaces should be front of mind for the designer. These are the elements that build social tissue, an essential ingredient in the successful transition to a higher density city.

USES BEYOND HOUSING

An NHS health centre is integrated into St Andrew's, providing more localised services. It has been designed to be central and open to the community with a roadside frontage and a main entrance facing a new public square, opposite people's homes. The centre accommodates a GP surgery, pharmacy and community health services open 7 days a week.

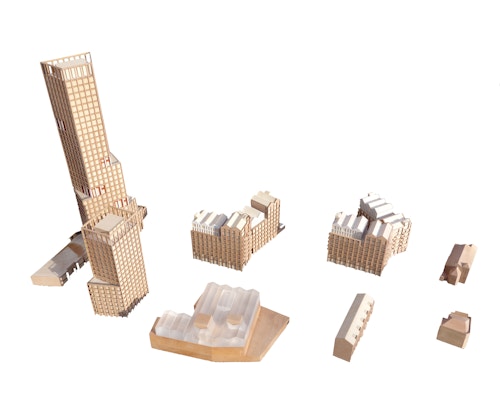

One urban plot, multiple building types: Camden Goods Yard

A lot on one plot

Camden Goods Yard reinvents a low-rise Morrisons supermarket and car park, from its current more suburban scale into an urban place more appropriate to the character and scale of its surroundings. The architecture embraces the much-loved yard and warehouse character of the north London context to greatly intensify an underutilised and isolated site, bringing it to life as a collection of eight new buildings, each visually distinct. They contain more than 570 homes from studios to 4-bed family units. There will be affordable workspaces, shops, and even a filling station. The supermarket will retain a store at the heart, sitting at the base of a new brick multiblock for living, working, shopping and farming. The roof will feature London's largest urban farm, specialising in growing peppers.

Supermarket integrated into housing

Living

Working

Morrison's Supermarket

Parking

Servicing

Public realm

The Old Kent Road is one of the ancient routes into central London. A working part of city, it is one of the GLA’s identified Opportunity Areas and will, in a few years’ time, be better connected into central London with the extension on the Bakerloo Line.

In this changing context, we drew up proposals for a low density site currently with light industrial use, which would transform it into a high-density urban block with remarkable typological diversity: more than 200 apartments across five blocks varying from three to fifteen stories, a terrace of ten houses and seven maisonettes peppered across the development. They are tied together by an assortment of cascading open spaces – private, shared and communal – found from ground to rooftop. Light industry, in the form of a local commercial laundry, would remain onsite, occupying pride of place on the ground floor.

Density, diversity and variety

On one block, five distinct typologies, housing and light industry

New residential courtyard

One urban plot, multiple building types: Keybridge

At Keybridge, nearly 600 homes occupy a tight London site where there previously stood an old telephone exchange. Three tall buildings (35, 21 and 19 storeys), three brick mansion blocks with maisonettes at street level and white terracotta-clad ones atop identifiable as individual houses, a further terrace of maisonettes, shops, a pub, business unit and an extension to the local primary school.

In form and scale, it's a contemporary smorgasbord of London vernacular traditions: one can find echoes of Georgian or Victorian terraces and utilitarian, through picturesque, warehouses and updates of the residential mansion. Every building is a purposeful response to each site edge resulting in an unusually rich typological ensemble that carves out interesting, irregular spaces.

New school integrated into Keybridge phase 2