Crafting urban identities

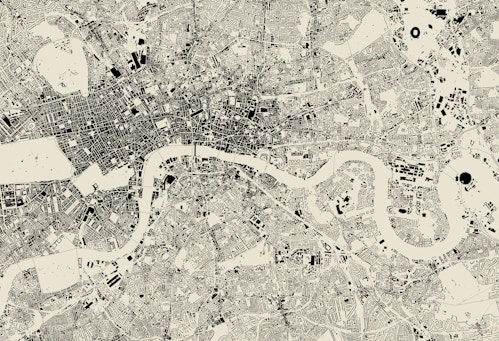

London's urban grain

Urban design benefits when it is in dialogue with diversity and geography. The tendency in masterplanning to rationalise the city can now be infused with data- and metrics-driven design, a diagrammatic and dialectical approach that has recently been applied across contexts. Yet the city is not a rational thing. It is an amalgamation of layers, of histories, of interests, of peoples. It is habitat. Masterplanning can recognise the uniqueness of every site’s context, the particularities of a city’s microclimate, whether temperate Toronto or tropical Singapore. Our understanding of a site should appreciate the nature of the topography underneath and the story of the place or places that preceded it. And in the absence of an established context, a good masterplan establishes a surrogate context – one though that defers to its geography.

LOOK OUT, NOT IN

Too many contemporary masterplans are so self-absorbed in their vision for the interiors of their sites that they fail to address the often much more significant, and much more difficult, issues pertaining to their wider contexts.

Toronto: covered galleria for all seasons and picturesque arrangement of buildings and spaces

Proposals for Jurong Lake District, Singapore

New vernaculars

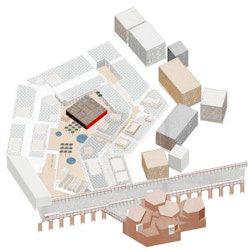

Msheireb is a city centre regeneration project involving the creation of an urban quarter of more than 100 buildings in the heart of Doha, a city that has experienced meteoric growth over the last thirty years. Our role has been to be the sitewide architectural voice within the masterplan team, crafting a new ‘Qatari’ language which bridges tradition with modernity, as well as serving as design architect for a number of individual buildings. Although very different in function and form, buildings and spaces across Msheireb include contemporary interpretations of traditional features such as internal streets and courtyards, decorative shading screens and the use of simple render and locally sourced stone. Sitewide, the tightknit urban grain is appropriate for the hot desert climate, allowing opportunities for shaded walkability.

COMPLEX SPACES WITH SIMPLE BUILDINGS

It is much easier to achieve complexity and richness within a masterplan by manipulating the relationships between buildings than to achieve it by forcing the shape and configuration of the buildings themselves.

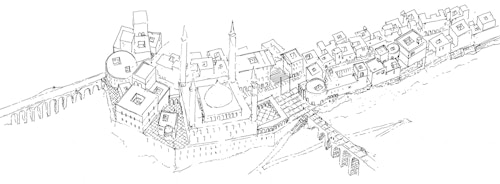

Old Doha

The masterplan for Madinat al Irfan, the urban extension for the Omani capital, has emerged from the country’s considered policy of sustainable development and promotion of its heritage. Design codes offer a core set of instructions that ensures new buildings and spaces will draw inspiration from the local vernacular, providing expression to Omani culture, instilling a strong sense of a city that will be grounded, permanent, unique. The urban form recalls the tight urban grain of older Arab cities, a climate-appropriate response that allows for shaded streets, co-locates uses and encourages walking. A Wadi Park at the heart of the scheme preserves the site's found riverine valley, which is a distinctive ecological system native to the Arab peninsula.

Madinat al Irfan, Muscat

Climate approriate architecture

Muscat: shaded public spaces and informal arrangement of buildings

Repurposing the pre-existing

The redevelopment of King’s Cross is an ongoing tale of dramatic reinvention. Despite its prime location in the shadow of two of London’s largest railway stations, it was once a no-go area of the city. Yet it possessed a remarkable industrial archaeology. While there are fifty new buildings, there are thirty retained buildings and structures across the estate. The Regent’s Canal (1812-20) bisects it. The two grand Victorian Stations – King’s Cross (1852) and St Pancras (1868) literally shape it. The Granary and Transit Sheds (1851) at its heart have been given new life as the new home for Central St Martins; Britain’s first purpose-built gym, the German Gymnasium (1865), is now a fashionable restaurant; Victorian gasholders have been integrated into new apartments; the old coal drops (1851-60) are now a retail galleria.

The retention and celebration of the area's industrial heritage provides for not just a memorable setting, but a narrative of place. What is fundamentally a new development catering to quintessentially twenty-first century occupiers such as Google, manages to retain a sense of character.

EXPLOIT THE POTENTIAL OF THE PRE-EXISTING

The history, topography and the climate of a site are important, not only because they help explain the nature of its past, but they can also inform the shape of its future.

King's Cross: old and new

Specificity and character

Major global cities turn to densification as they literally run out of space. The acute need to recycle existing urban land generates large new developments that are altering the fabric of these cities.

In London, our characterisation and density study for Historic England uncovers and catalogues the city's rich layers of existing character. The report identifies sixteen character types, from the ancient Roman core to Georgian Growth to Victorian Entrepreneurship to twentieth century suburbs.

Through a comprehensive mapping of the city, our research illustrates how these different layers transcend London’s central, urban and suburban areas. Each character type has been shaped by various factors, including transport links, ever shifting planning regulations and history – and together, they are uniquely London. These findings could shape a character-based approach to densification that is bespoke to London’s complexity. Indeed, it is a localised approach that other cities could adopt.

PRIORITISE SPACE OVER FORM

In Japanese calligraphy, the space formed by the brushstroke is as important as the shape of the line: in a masterplan the focus must be as much on the space between buildings as it is on the buildings themselves.

Victorian entrepreneurship, London